Painting Profits: A Call Option on the Ultra Wealthy

As Jack Hough puts it: Van Gogh is the guy whose fields look swirly; if it’s a party scene, and people look happy – Renoir. If they look unhappy – Manet. Ballerinas = Degas. If everyone is naked and physically fit – Michelangelo. Naked with large tushes? Rubens. If it looks like you’re on a hallucinogen, it’s a Dali. If body parts have migrated to strange places – either you’re on a hallucinogen or it’s Picasso’s later works.

My friends have been sending me links to Masterworks, and some have asked if they should invest. I asked myself the same question – I created an account, set up a call, and drilled some questions (well answered, I will say). This podcast episode did an excellent job in explaining it. I wanted to share it with you.

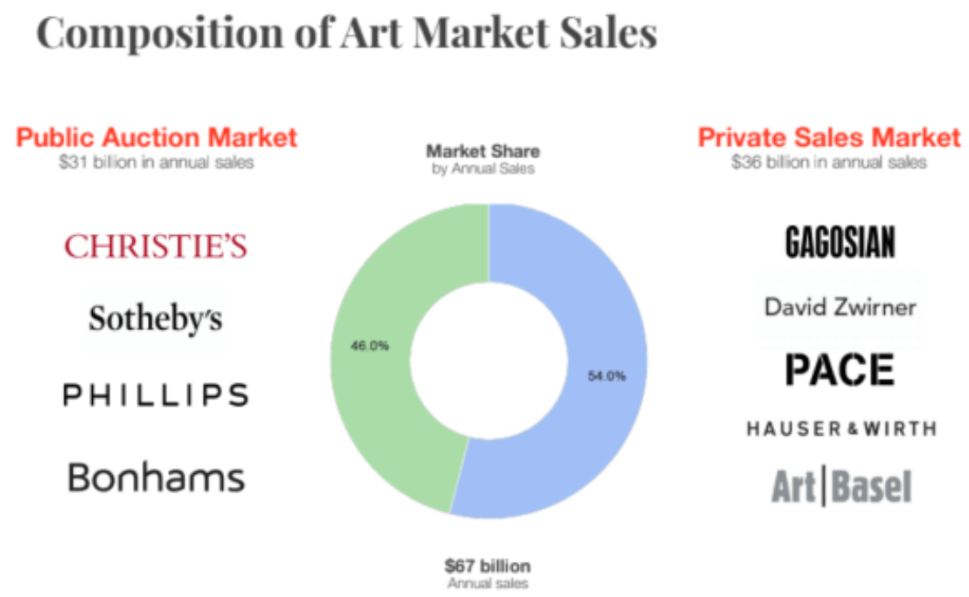

In our lifetimes, we will see a painting sell for $1 billion following the $450.4 million da Vinci sale. The art market was estimated at $1.7-2.0 trillion with ~$67 billion in sales in 2017. Half of art is exchanged privately, the other half flirts with numbered paddles. Most of it is expensive.

How do we get in on this? If we don’t want to treat ourselves to a $1 million Condo, we can dabble with Masterworks. Masterworks is a 3-year old NYC-based platform claims to democratize access to fine art. An expensive painting is “sold” into tiny shares. No one gets to hang the painting, but participates in the profits if the price goes up.

This is called securitization. For each painting, it creates a special holding company that buys, cares for, promotes and eventually sells the painting. Masterworks sells shares these holding companies. As with any IPO, it files forms with the SEC that fills the public in on these paintings. Management fee is ~2% to cover storage, insurance, overhead, etc. And similar to owning shares of a company stock, you can sell your shares before the painting is resold (3-7 years). The fund is run like a PE fund in 2/20 structure.

Risks stated in these prospectuses include: the painting is “highly subjective”, and “we may have overpaid for this painting”. Yes and yes. How do you know if you overpaid for this painting? What even gives a painting its value?

This is something I’ve written about a few times, but I do love coming back to it. Supply and demand, of course, but there are no cash flows or underlying asset values to tell if valuation is out of WACC (ha).

Mark Rothko, in Hough’s example, is a famous painter (and recent addition to my condo! See photo) who died fifty years ago. He painted giant hazy, murky boxes in different colours. Not even any big tushes or ballerinas. In 2014, a Rothko with three hazy boxes sold for $4 million. We’ll call that $1.3 million per box. That same year, a two-box Rothko reportedly owned by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen went for $56 million. Hmm – price to box (“P/B”?) ratio isn’t very consistent. That being said, if you get the chance to, sit in the Rothko room in the Tate Modern.

Rothko Room in the Tate Modern

Masterworks founder Scott Lynn says the top correlation with appreciation rate is the artist. If you choose the wrong artist, it doesn’t matter how great the painting is. I say this is similar to brands – the same reason a black lambskin bag won’t compete with a Chanel.

This year Masterworks identified ~45 artists that are most appreciable. The company tracks around 1,100 paintings, focusing on momentum buying. “The reality is that our market is not that sophisticated,” he says. “We’re the only research team in the art market that analyzes returns. That in itself is shocking.”

One way to think of art, Lynn says, is as a call option on the ultrawealthy. If the rich will continue to become even richer, they will pay even more for paintings. When artists die, their paintings are donated to museums and declines supply – this further boosts prices.

Early this year, Masterworks published a report showing that in back-testing, its Target Artists index returned 10.7% a year, over the past 20 years. Global stocks returned 5%, and U.S. houses, 3.9%. However, Houghes has a few reservations. This includes the disposition bias. Namely that indexes generally track transaction prices, and focus on paintings that come to market relatively often. The problem is that investors are quick to sell things that have gone up in value, but tend to cling to things that have gone down, holding on to hope. And its presence introduces selection bias in measuring art returns, or returns for things that trade infrequently (unlike stocks), including houses. and used sneakers.

I did not end up investing after that call with Masterworks. It’s still on my mind though and I may put in some funds to spice up my portfolio. I definitely think it’s a clever concept. That being said, I believe that Lynn and his team are the real ones profiting from other people supplying the capital to buy their paintings plus netting a 1.5-2% management fee. All the power to them! Art funds are very clever structures (next post) and after building a model for one, it made me realize how very clever they are.

Hope this provided some clarity and / or made you think. As always, love to hear your thoughts.

Katya