Learned Optimism

Today we’re talking about optimism. I’m reading this book called Learned Optimism by Martin Seligman and I like it. Learned Optimism digs into why optimists are healthier, happier, and more successful people than pessimists; how both are learned attitudes and what you can do to become an optimist yourself.

I found this so valuable as it found the loophole in my ever-optimistic but incredibly self-critical nature - give it a read to see if it reframes your thinking.

There are two key concepts here: learned helplessness and explanatory style.

Learned Helplessness

Learned helplessness is the giving-up reaction, the quitting response that follows from the belief that whatever you do doesn’t matter. It is a phenomenon observed in both humans and animals when they have been conditioned (aka experimented upon) to expect pain, suffering, or discomfort without a way to escape it.

Eventually, the animal will stop trying to avoid the pain at all, even when there is an opportunity to truly escape it. They begin to think, feel, and act as if they are helpless. This leads to depression.

However, this is not an innate trait. No one is born believing that they have no control over what happens to them and that it is fruitless even to try gaining control. It is a learned behavior, conditioned through experiences in which the subject either truly has or believes that he has no control over his circumstances. Many experiments concluded that, on average, two out of three test subjects gave up in helplessness.

However, a man nameed John Teasdale rebutted. Yes, he said, two out of three people became helpless. But one out of those three resisted: No matter what happened to make them helpless, they would not give up. Why?

Explanatory Style

Seligman’s team attributed this to explanatory style: the manner in which you habitually explain to yourself why events happen. The habits of explanation (not just a single explanation a person makes for a single failure) and the style of seeing causes.

They began to consider how optimism and pessimism were related to how people explained the cause of challenges and adverse events.

According to Seligman’s explanatory style definition, “The basis of optimism does not lie in positive phrases or images of victory, but in the way you think about causes.”

Learned optimism is not a rediscovery of the “power of positive thinking”. What is crucial is what you think when you fail, using the power of “non-negative thinking”. Changing the destructive things you say to yourself when you experience the setback that life deals all of us - optimists and pessimists - is what is the central skill of optimism.

The team came up with a questionnaire to measure explanatory style based on three dimensions: permanence, pervasiveness and personalization.

Permanence

Bad Events

People who give up easily believe the causes of bad events that happen to them are permanent - the bad events will persist, will always be there to affect their lives, never to change. Those who believe bad events are temporary, resist helplessness. Permanence is about time.

Failure makes everyone momentarily helpless. But those who don’t shake the hurt off, remain helpless for days or months, even after only small setbacks. Permanence helps indicate why some people stay helpless forever while others bounce back right away. For example, you did 20 things well at work today, but the one thing you got feedback on, you outweigh in your mind and draw the conclusion that “you’re bad at your job”.

Good Events

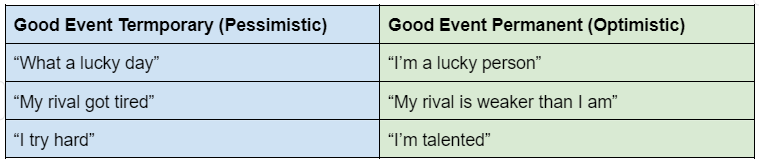

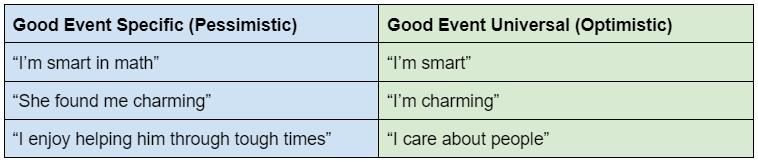

The optimistic style of explaining good events is the opposite style of explaining bad events. Those who believe good events have permanent causes are more optimistic than those who believe they have temporary causes.

Optimistic people name permanent causes: traits, abilities, always’s. Pessimistic people name transient causes: moods, effort, sometimes’s. People who believe good events have permanent causes try even harder after they succeed.

Pervasiveness

Bad Events

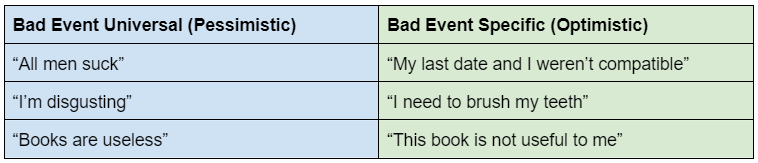

Pervasiveness is about space. Some people can put their troubles neatly in a box and go about their lives when one important aspect of it (job, love life, etc.) is suffering. Others bleed over everything.

This comes down to when you make a universal explanation for failures, giving up on everything, instead of making a specific explanation to become helpless in that one part of your life. This can often indicate if you are a catastrophizer.

Good Events

Finding temporary and specific causes for misfortune is the art of hope. Temporary causes limit helplessness in time, and specific causes limit helplness to the original situation. All is not lost. Finding permanent and universal causes for misfortune is the practice of despair, crushing people under pressure for a long time and across situations.

Personalization

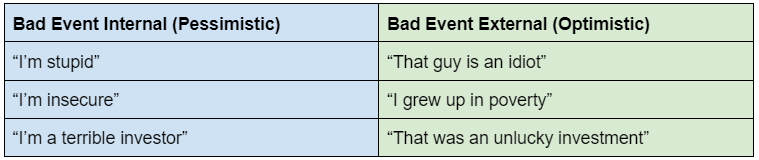

Finally, personalization is whether you externalize or internalize events. Although I rank highly on the other two as an optimist, I ranked incredibly low on this dimension - I internalize bad events and I externalize good events…This one was an eye-opener for my usually peppy, rose-glasses self.

Bad Events

When bad things happen, we can either blame ourselves (which adds up, every single time) or we can blame other people and circumstances (externalize). According to Seligman, people who blame themselves when they fail repeatedly have low self-esteem - they may think they are worthless, talentless and unlovable. People who blame external events do not lose self-esteem when bad events strike.

While I see Seligman’s point, I believe there is a lot of value to owning up to mistakes that you actually did influence and taking ownership of them. There definitely is damage to society by the erosion of personal responsibility, evading duties to chase after “personal fulfillment”, etc. However, specifically with depression, Seligman found that depressed people often take much more responsibility for bad events than is warranted. The “balance” must be found to ensure that you take responsibility for what you do (internal style) but believe the cause of the bad event can be changed (temporary style).

Good Events

On the other hand, those who internalize good events tend to like themselves more than those who believe good events come from other people or circumstances.

Again to caveat, I think there is a lot of value in not attributing all successes to yourself and recognising both others’ contributions and that of pure luck. However, patting yourself on the back and tooting your own horn (when necessary) is important too - and something a lot of women can improve at.

If your explanatory style optimistic or pessimistic?

When you add the results up for the categories in his test, you have an ultimate score. If you rank highly towards optimism, congratulations! If you score as a Pessimist, Seligman states there are four areas where you will encounter trouble:

You are likely to get depressed easily

You are probably achieving less at work than you talents warrant

Your physical health / immunity could be better and may get worse as you get older

Life is not as pleasurable as it should be

If you’ve made it this far, congratulations - a next piece will help you to choose to raise your everyday level of optimism. Do not despair! You will find yourself reacting to the normal setbacks of life much more positively, bouncing back faster, achieving more, and feeling physically better. Although it spooked me ranking so pessimistically on the last category of Personalization, it felt good to know my weakness and that it is possible to strengthen it. I hope this helps you to frame your mind as well.

Katya